Most vertebrate paleontologists probably think of the spectacular dinosaur finds near Jensen, Utah, when the name Earl Douglass is mentioned. Douglass’s discovery of a partial Apatosaurus near Jensen in 1909 did spark the beginning of his long career with finding more dinosaur material in what we now know as Dinosaur National Monument. But Douglass began his quest for fossil vertebrates while he was in southwestern Montana – several years before he was summoned by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s director William Jacob Holland to find dinosaurs.

From the spring of 1894 to 1896, Douglass taught at a one-room school in the lower Madison Valley of southwestern Montana. The school house was located in the lower Madison Valley, directly west of the area known as the Madison Bluffs. These bluffs contain strata that range in age from probably as old as Eocene through the late Miocene. The strata are continental units that include alluvial fan to fluvial trunk stream deposits.

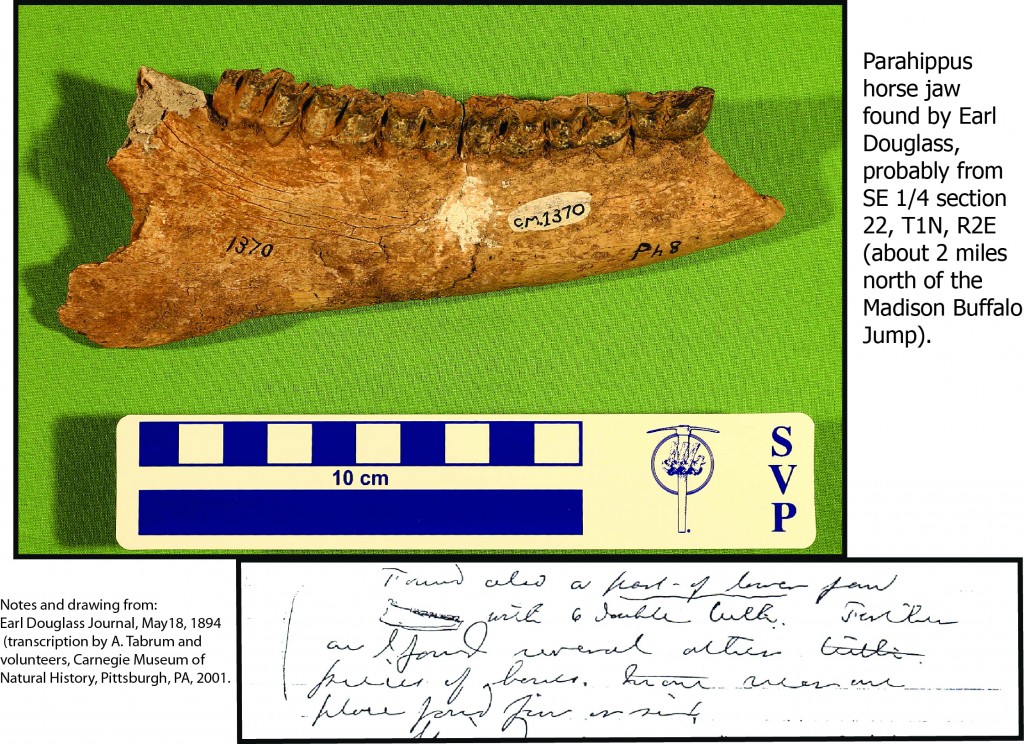

During his tenure at the lower Madison Valley school, Douglass spent much of his spare time exploring the Madison Bluffs. At the beginning of his teaching contract in 1894, he had very little knowledge of vertebrate paleontology and of the area geology. He initially considered the Madison Bluff beds as Cretaceous in age. But when he found a “tooth very much like a Protohippus” (Earl Douglass journal entry on May 12, 1894), Douglass knew that the beds were younger in age. As time passed, he began to find a significant quantity of fossil vertebrate mammal material within the bluff’s deposits. Consequently, he immersed himself into reading about comparative anatomy so he could readily identify the fossil material. Douglass eventually used his collected fossil material for his 1899 Master’s thesis at the University of Montana – ostensibly the first Master’s degree awarded by the University.

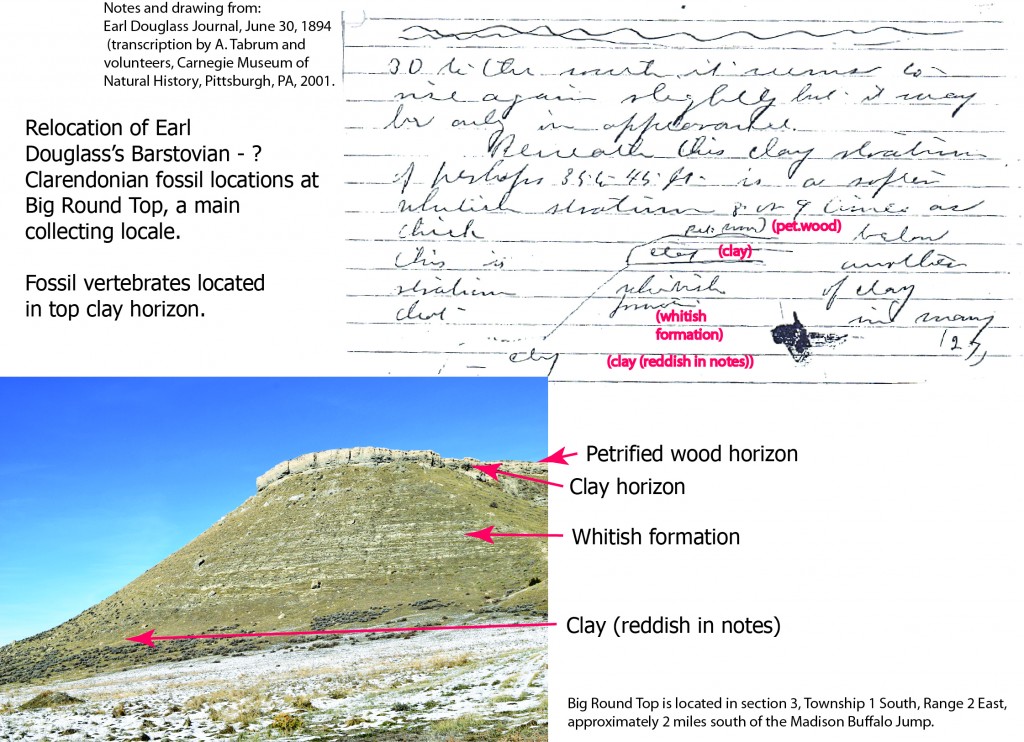

Douglass kept journals of his time in the lower Madison Valley, and often detailed both the area geology as well as his fossil finds. Alan Tabrum and volunteers from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have transcribed many of his journal entries from southwestern Montana. I’ve included two portions of journal entries to illustrate his finding of a horse jaw from the bluffs (above diagram) and one of Douglass’s drawings of “Big Round Top” (an area in the bluffs near the one-room school house) as compared to that same area today in a photo that I took about a week ago.

It’s not difficult to understand how Earl Douglass became enthralled with the geology and paleontology of the Madison Bluffs. In addition to the fossil vertebrates, the bluffs contain many other fascinating geological features. Towards the central part of the bluffs (immediately south of the Madison Buffalo Jump State Park), calcic paleosol stacks mark the boundary between most likely Eocene and Miocene strata. The calcic paleosol stacks contain at least two generations of soil profiles (typically minus the A and upper part of the B horizons). Rootlets and burrows are commonly associated with these paleosols.

Volcanic tuffs also occur within the bluff’s strata, which is really handy for those of us who like isotopic age control for southwestern Montana Tertiary deposits. The tuffs could potentially help age constrain the paleosol stacks and sedimentation within the so far non-fossil bearing part of the bluffs. And with the help of the New Mexico Geochronology Lab, a group of us are working on just that aspect of Madison Bluff geology.