Iceberg Lake is situated in the Many Glacier area of Glacier National Park. The hike is about a 10 mile round trip and gains about 1275 feet in elevation. The trail winds through prime grizzly bear habitat, so be sure to hike with a group, make lots of noise, and carry bear spray. It would also be good to get a strong bag or pack that can withstand a bear attack (click the following to learn more) because if one punches a hole in a weaker bag, it could mean bye-bye bear spray. When I hiked the trail back in September, many returning hikers told our group about a grizzly sow and two cubs that were roaming around by Iceberg Lake. The bears actually walked by the lakeshore while my group and many others were at the lake, but there were no harmful encounters. However – just this past week, in this same general area, a sow grizzly with 2 sub-adult cubs (I’m guessing that this is the same set of bears that walked by my group at Iceberg Lake) was surprised by a lone hiker and the sow grabbed and shook the hiker. The hiker used his bear spray escaped with puncture wounds to his lower leg and a hand. So – some words of caution about hiking in bear country!

The Iceberg Lake Trail

The trailhead to Iceberg Lake is behind the cabins near the Swiftcurrent Motor Inn. The first part of the hike, about 1/4 mile, gains about 185 feet. After that initial elevation gain, the trail’s elevation gain moderates. Ptarmigan Falls is about 2.5 miles from the trailhead, and a short way above this is a footbridge that crosses Ptarmigan Creek. The rocky area near the footbridge is a great place for a snack break. Another 1/10 mile beyond the footbridge is the Iceberg Lake Trail junction. The Ptarmigan Trail continues towards the right and goes to Ptarmigan Tunnel and Ptarmigan Lake.Take the other trail branch to continue on to Iceberg Lake. A good trail hike summary for the Iceberg Lake Trail is found at the website “Hiking in Glacier”.

The popularity of the trail was clear to me when even on a rainy, sleety, and snowy day,I passed many people on the trail. My group did a leisurely hike, stopping at several places to look at the geology alongside the trail and to do a snack stop by the Ptarmigan Creek footbridge both on the way up and back. It took us about 5 hours for the round trip. That put us back just in time to have a much enjoyed dinner at the Swiftcurrent Motor Inn.

The Iceberg Glacier: Recession from 1940 to the Present

The Iceberg Glacier is shown in the above photo set beginning in 1940 (this is the photo on the left, which is a Hileman photo from the Glacier National Park Archives) and ending with the 9/6/2015 photo on the right, which I took during my hike to Iceberg Lake. In the 1940 photo, the glacier terminus is quite thick and extends into the basin. By 2015, there is not much left of the glacier. Even with a comparison between the center 2008 photo by Lisa McKeon and my 2015 photo, one can see that much more bedrock is exposed. The older photos are also posted on the US Geological Survey’s Repeat Photography Map Tour Website. For those interested in glacial recession within Glacier National Park, the Repeat Photography website is a valuable resource. The Repeat Photography project is summarized on the USGS website –

This project began in 1997 with a search of photo archives. We used many of the high quality historic photographs to select and frame repeated photographs of seventeen different glaciers. Thirteen of those glaciers have shown marked recession and some of the more intensely studied glaciers have proved to be just 1/3 of their estimated maximum size that occurred at the end of the Little Ice Age (circa 1850). In fact, only 26 named glaciers presently exist of the 150 glaciers present in 1850.

Trail Geology

Much of the Iceberg Lake Trail winds through the Grinnell Formation, which is a Proterozoic geologic unit within the Belt Supergroup. As Callan Bentley has succintly said of the Belt Supergroup rocks in Glacier National Park:

The rocks exposed firstly from the top down are old sedimentary rocks of the Belt Supergroup. It is called “Belt” after Belt, Montana, and “supergroup” because it is immense. These rocks were deposited in a Mesoproteozoic (1.6-1.2 Ga) sea basin, and show little to no metamorphism despite their age.

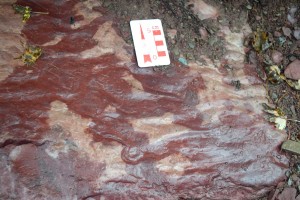

I was lucky to be hiking with Jeff Kuhn from Helena, Montana, who has done much work with Belt Supergroup rocks in the Glacier Park to Whitefish Range areas. Jeff stopped us at several locations along the trail to look more closely at features within the Grinnell Formation. In general, the Grinnell Formation consists of sandstone and argillite and is approximately 1740-2590 feet thick. It has a deep brick-red color owing to its contained hematite and because it was deposited in a shallow oxygen-rich environment. Sedimentary features that are consistent with the shallow water depositional interpretation include mudstone rip-up clasts, mudcracks, and ripple marks.

All told, it was a hike well worth doing, even if you are not a geology enthusiast!